A history resource article by Mary Harrsch © 2015 and 2017

It seems that every time the Roman Empire is discussed someone always points out the number of slaves that were exploited by Roman citizens as if the Romans invented slavery. One thing that was unique about Roman slavery compared to slavery in other parts of the ancient world is the Romans had a structured process of social advancement that provided a means for slaves to become freedmen through the procedure called manumission. Scholars have debated just how often manumission was used in Roman Society and how many slaves were freed as a result.

"The institution of slavery has served to perform different functions in different societies. The distinction between 'closed' and 'open' slavery can be a useful one: in some societies, slavery is a mechanism for the permanent exclusion of certain individuals from political and economic privileges, while in others it has served precisely to facilitate the integration of outsiders into the community...The model of an 'open' slavery implies that service as a slave is not a state to which a person is permanently, let alone 'naturally', assigned but more akin to an age-grade." - Thomas, E. J. Wiedemann, "The Regularity of Manumission at Rome"

A Roman slave, on formal manumission, was granted Roman citizenship and thereby formally integrated into Roman society. So how does this contrast with other ancient slave-owning societies like the Greeks?

"Greek commentators on Roman customs thought that the extent to which the Romans practised manumission was highly peculiar; but although they refer to the number of slaves the Romans freed, what really surprised them was that such great numbers of persons of servile origin should be integrated into the Roman state as citizens." Thomas, E. J. Wiedemann, "The Regularity of Manumission at Rome"

The most common form of manumission was termed the Manumissio vindicta.

"In this, the most commonly practiced form of manumission, the master, the slave, a third party, and a praetor gather to manumit the slave. The third party member lays a freedom rod, called a vindicta , on the slave pronouncing the slave free. The master then follows suit by placing his or her vindicta on the slave while the praetor witnesses both performing this action to the slave." - Brendan Patrick Sheridan, Miami University, Roman Slavery

Another common method of manumission was called the Manumissio testamento.

"In this form one of two things can happen: In the first condition, a slave is set free by a proclamation to do so in the master's will. In the second condition, the master entrusts his slave to another freeperson on the grounds that upon doing so, the slave be set free by the new master. In the second condition, the slave may not be immediately set free because the slave will only be freed when the new master frees him or her, and, until the slave is freed, the slave is classified as a statuliber." - Brendan Patrick Sheridan, Miami University, Roman Slavery

The third method of manumission was known as Manumissio censu.

"In this form, the slave goes before the censor and proclaims to be a freedperson [with witnesses and/or evidence], at which time, if the censor agrees, the censor will record the slave's name down as a freedperson, and thus the slave will be manumitted." - Brendan Patrick Sheridan, Miami University, Roman Slavery

Roman slaves were allowed to manage some personal property, often a small wage called a peculium.

"This peculium could consist of a myriad of things including money and a slave's slave called a vicarius. The peculium could be used by the slave in many ways, but the slave was restricted in that all contracts entered by the slave involved the master, and the slave could not give his peculium to someone else so that the other person might use it to buy the slave's freedom. The slave could save peculium and buy its freedom, but this usually only happened when the peculium outweighed the slave's value." - Brendan Patrick Sheridan, Miami University, Roman Slavery

Although manumission was treated as a sought after privilege, it was not always altruistically granted. Elderly slaves were sometimes manumitted because they were no longer productive and their masters no longer wished to provide for them. If a slave was privy to incriminating information, a master might manumit them to avoid the slave providing incriminating information under torture. Slaves were also sometimes promised manumission if they served as soldiers in civil insurrections.

So, how often did manumission occur? That question has consumed scholars for decades!

"In 357 BCE Rome passed a law called the Lex Manlia imposing a manumission tax. Freeing slaves from then on would incur a 5% fee. Because 5% is one-twentieth, the tax was referred to as a Vicesima. (Livy VII.16)

This legislation was initially proposed by the consul Gnaeus Manlius Capitolinus while encamped with his army so it is said to have been passed "in castris." The purpose of the law was to reduce the number of manumissions, both the freeing of slaves and the manumission of children since it was feared some families would use manumission of their minor children to gain access to more land since there was also a 500-acre limit per male head of household specified in another law included in the Leges Liciniae Sextiae passed at that time.

H.H. Scullard, in A History of the Roman World 753-146 BC (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1980) says that based on records of these taxes, by 209 B.C.E., an estimated 1350 slaves may have been manumitted each year."

But that was more than 100 years before the widespread conquests of the Late Republic.

Apparently, the Lex Manlius had little effect on the rate of manumission even as numbers of slaves dramatically increased. Freeing slaves in an individual's will had become so widespread in the late Republic that in 2 BCE the Lex Fufio-Caninia was passed limiting the number of slaves a citizen could free in their wills.

"The Fufia Caninia made the number of testamentary grants of freedom permitted to cives Romani dependant upon the total number of slaves owned by any one Roman citizen master. One who owned from three to ten slaves was permitted to manumit one-half of them in his will; one who owned eleven to thirty, one-third of the total. If the slaves of the Roman citizen numbered from thirty-one to one hundred, he might free one fourth of them; if their numbers ran one hundred to five hundred only one in five or twenty percent, might be freed by testamentary manumission. The law further provided that no Roman citizen could free by testament more than one hundred, however many slaves he might have." - William Linn Westermann, The Slave Systems of Greek and Roman Antiquity

Six years later this law was further amended by the Lex Aelia-Sentia that restricted the rights of Roman youths under the age of 20 to free their slaves and specified that only slaves over 30 years of age could be freed although there was a mitigating provision that an exception could be granted of approved by a committee of ten persons made up of five senators and five equites. Modern scholars think Augustus promulgated these laws due to the influence of Dionysius of Halicarnassus. The esteemed historian Dionysius had pointed out that many freedmen were enriching themselves from sordid occupations such as robbery and prostitution and emphasized the danger of allowing their proliferation in the city of Rome. Being a Greek, Dionysius probably ascribed to the Athenian perspective on slave manumission. In Athens, slaves could be manumitted but were not granted citizenship as under Roman law. Athenian freedmen could not partake in government or bear free children.

Under Roman law, although freedmen were barred from the cursus honorum, they could vote in city assemblies and their children would be considered free citizens with full rights of Roman citizenship. The isus sacrum which allowed slaves to practice certain aspects of religion, to be properly buried and to join certain religious associations was further amended in the 1st century CE to allow freedmen to become priests in the emperor cult. These religious magistrates became known as the Augustales.

Like most things in life, there was a major exception to the granting of these rights, however.

"The Lex Aelia Sentia requires that any slaves who had been put in chains as a punishment by their masters or had been branded or interrogated under torture about some crime of which they were found to be guilty; and any who had been handed over to fight as gladiators or with wild beasts, or had belonged to a troupe of gladiators or had been imprisoned; should, if the same owner or any subsequent owner manumits them, become free men of the same status as subject foreigners (peregrini dediticii)... "

"...'Subject foreigners' is the name given to those who had once fought a regular war against the Roman People, were defeated, and gave themselves up...."

"...We will never accept that slaves who have suffered a disgrace of this kind can become either Roman citizens or Latins (whatever the procedure of manumission and whatever their age at the time, even if they were in their masters' full ownership); we consider that they should always be held to have the status of subjects." - Selections from the Lex Aelia Sentia

But what does the archaeological record tell us about actual numbers of freedmen in relationship to other social groups?

G. Afoldi, citing a 1972 study of Roman-era inscriptions found in Italy in his paper Die Freilassung von Sklaven und die Struktur der Sklaverei in der romischen Kaiserzeit (The release of slaves and the structure of slavery in the Roman Empire), discovered that of 1,126 persons of servile origin who died before the age of 30, 59.3 percent were freed, 40.7 percent were still slaves. Of 740 persons who died over the age of 30, 89.3 percent were freed, and only 10.7 per cent had remained slaves. He concluded that, in view of these statistics, a slave could probably count on being freed as a matter of course.

However, Thomas E. J. Wiedemann, in his 1985 article "The Regularity of Manumission at Rome" expressed his opinion that Afoldi's inscriptions represented a highly atypical sample.

"Slaves who did not have the qualities to attain manumission were clearly less likely to be commemorated by means of a (relatively detailed, therefore costly) inscription; slaves who were considered fideles, but died young, might be so commemorated. More particularly, a freed slave's heirs would be keen to preserve a public record of his manumission in the form of a funerary inscription. Futhermore, these inscriptions give undue emphasis to those slaves and freedmen who had easy access to their dominus. As Alfoldi noted (p. 116) 98 percent of the surviving inscriptions are from the context of the familia urbana. The obvious explanation for why so few freedmen are attested from the familia rustica is that very few agricultural slaves were actually freed."

Any analysis of extant funerary inscriptions may, by its very nature, carry a bias due to the cost of an inscription, especially considering the fact that we are attempting to draw conclusions about a community's lowest social tier from them. Agricultural slaves had far fewer opportunities to amass savings than slaves in an urban setting. Perhaps inscriptions for them are missing from the archaeological record because they simply couldn't afford such expensive monuments. Other unknown contributing factors could be deaths from pestilence where victims, from necessity, were disposed of in communal pyres or pits and whose relatives did not survive either and reuse as building material in later centuries.

Weidemann also dismisses an analysis of epitaphs from imperial slaves indicating that manumission was regularly achieved between the ages of 30 and 35.

"The imperial household was not just different in scale from others; it also followed different procedures of manumission. The legal restrictions did not apply to the emperor; his slaves were not manumitted vindicta or testamento, but simply declared to be free," Wiedemann observes.

A study of the Osyrhynchus Papyrir (up to vol. XLII) from Roman Egypt revealed of 46 slaves or freedpersons ranging from 3 to 65 years, 8.3 percent of those under 30 had been freed but of those over 30, fully half had been freed. Wiedmann points to the small sample size, though, as insufficient to provide meaningful statistical evidence.

Wiedemann then turns to the literary record to examine Roman society's acceptable norms for manumission. Citing two examples in Martial's epigrams, Wiedemann concludes, "A Roman wanted to believe that if a slave served him faithfully, he would be rewarded with the freedom he deserved."

He goes on to point out though, "If manumission was the due reward of the servus fidelis, then it followed that a slave-owner did not have any obligation to free a slave who had demonstrated that he was not fidelis. There is plenty of evidence that masters who were displeased with their slaves would include in their wills a clause prohibiting slaves in question from ever being freed...Thus the ideal that loyal service deserved manumission also implied that a master might be acting justly if he refused to free his slaves: he need have no moral compunction so long as he persuaded himself that his slaves had failed to show him the loyalty a master deserved (cf. 'nullo merito meo'). One suspects that the formula 'nulla fides > nulla manumissio' may have been adduced very much more frequently in real life than the formula 'fides > manumissio'."

I think this viewpoint that Rome's wealthy slave owners were probably too greedy to reward faithful slaves with manumission does not take into account the fact that freed slaves were not simply allowed to go their separate ways when manumitted. The prevailing practice was for freed slaves to become clients of their former master.

"Roman societal patronage was highly based around the Roman ideals of fides or loyalty. Clients were loyal supporters of high standing families and at the head of those families were the patronus, or their patron. For this loyalty, the patron rewarded their loyal clients with gifts of food and land. If a client needed any sort of legal representation or aid they called upon their patron for support. Patrons often handed out sportulas, which were monetary handouts for their support and loyalty. The patron received not just loyalty from their clients but they also had the respect, men for guarded escorts, and their political support." - Roman Patronage in Society, Politics, and Military, a collaborative website of Pennsylvania State University

Another issue not mentioned in the above quote is the operation of businesses that produced income for the patrician class. Patricians were not supposed to engage openly in business activities so these revenue-generating activities had to have the appearance that they were being operated by others. These positions could be held by freedmen. Patrons not only provided monetary handouts for a client's support but also provided loans for businesses operated by their freedmen-clients.

Add to this the problem of a slave-owner appearing to be greedy if slaves were not freed while reasonably young.

Wiedemann states, "In his invective against Piso, one of the grounds on which Cicero attacks him is his parsimoniousness. He argues that, while a luxurious lifestyle is, in principle, immoral, there is a particular kind of luxuria (conspicuous consumption) which is expected of a public figure. But this was not to be found in Piso's household; Piso was so unwilling to put his wealth to public use that he was not even prepared to spend money to acquire any new slaves, so that (In Pisonem 67):

servi sordidi ministrant, nonnulli etiam senes; idem coquus, idem atriensis (the servants who minister to the mean station positions, some even old men; the cook is the same thing, the same as the doorkeeper)

Although Wiedemann thinks Cicero is referring to the generally recognized custom that slaves who serve at a banquet ought to be young and handsome, I must point out his quote also refers to the cook and the doorkeeper, not usually present in the banquet setting.

"For the Roman upper aristocratic ruling class public appearance was extremely important. When traveling through the city and the forum the Roman elite desired to be recognized or recognized for their status and rank. To accomplish this they wore distinctive clothing and jewelry to help signify their status. Equestrians wore specifically colored cloth stripes on their togas or tunics to signify their statuses. The senators and patricians also wore wider specifically colored cloth stripes to signify their rank. The upper-class patrons wanted to show they had power and made certain to remind their clients of this by their mannerisms and dress." - Roman Patronage in Society, Politics, and Military, a collaborative website of Pennsylvania State University

So, if slaves were regularly manumitted after a period of service, what was the socially acceptable length of time a slave could expect to serve? Wiedemann examines a number of legal cases and finds several references to periods of five years although that may be an average as a number of cases cite longer periods and some even shorter periods.

Perhaps more telling is a quote from Cicero's Eighth Philippic in which Cicero exhorts the Senate to resist Antonius' dictatorship.

Etenim, Patres conscripti, cum in spem libertatis sexennio post sumus ingressi diutiusque servitutem perpessi quam captivi servi frugi et diligentes solent (In fact, Conscript Fathers of the Senate, I have the hope of freedom, that after six years, we are good and diligent slaves taken in war and have endured slavery longer than the customary [period].

Cicero is referring to the six years since Gaius Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon but uses its length of time as a metaphor for a slave's length of servitude.

Wiedemann points out, "Clearly Cicero could not use this analogy between slavery and submission to the rule of Caesar and Anthony if his senatorial audience did not believe that it was reasonable for a slave-owner to grant freedom after he had had possession of a slave for six years of adult labour — assuming of course that the slave was frugi et diligens."

So it appears slavery in Rome was not a lifelong sentence as in other ancient cultures and manumissions occurred regularly.

References:

Thomas E. J. Wiedemann. (1985). The Regularity of Manumission at Rome. The Classical Quarterly, 35(1), 162-175. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/638813

Patrick, B. (n.d.). Roman Slavery. Retrieved August 11, 2017, from http://www.vroma.org/~plautus/slaverysheridan.html

Aföldi, G. (1972). Die Freilassung von Sklaven und die Struktur der Sklaverei in der romischen Kaiserzeit (The release of slaves and the structure of slavery in the Roman Empire). Rivista Storica dell' Antichitá , 2, 97-129.

Roman Patronage in Society, Politics, and Military. (n.d.). Retrieved August 11, 2017, from https://sites.psu.edu/romanpatronagegroupdcams101/societal-patronage/

Collaborative website of the Classics Department of Pennsylvania State University

A Kindle preview of a bit of a tongue-in-cheek guide to Roman slavery:

Additiional suggested reading:

|

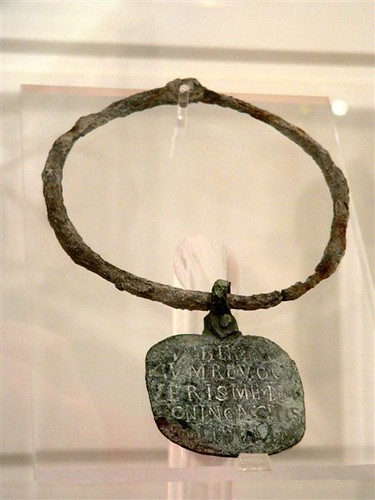

| A Roman slave medallion at the Baths of Diocletian venue of the National Museum of Rome. Photographed by Mary Harrsch © 2005 |

"The institution of slavery has served to perform different functions in different societies. The distinction between 'closed' and 'open' slavery can be a useful one: in some societies, slavery is a mechanism for the permanent exclusion of certain individuals from political and economic privileges, while in others it has served precisely to facilitate the integration of outsiders into the community...The model of an 'open' slavery implies that service as a slave is not a state to which a person is permanently, let alone 'naturally', assigned but more akin to an age-grade." - Thomas, E. J. Wiedemann, "The Regularity of Manumission at Rome"

A Roman slave, on formal manumission, was granted Roman citizenship and thereby formally integrated into Roman society. So how does this contrast with other ancient slave-owning societies like the Greeks?

"Greek commentators on Roman customs thought that the extent to which the Romans practised manumission was highly peculiar; but although they refer to the number of slaves the Romans freed, what really surprised them was that such great numbers of persons of servile origin should be integrated into the Roman state as citizens." Thomas, E. J. Wiedemann, "The Regularity of Manumission at Rome"

|

| Gravestone of a high status woman with her slave attendant Greek 1st century BCE Marble. Photographed at the Getty Villa by Mary Harrsch © 2014 |

"In this, the most commonly practiced form of manumission, the master, the slave, a third party, and a praetor gather to manumit the slave. The third party member lays a freedom rod, called a vindicta , on the slave pronouncing the slave free. The master then follows suit by placing his or her vindicta on the slave while the praetor witnesses both performing this action to the slave." - Brendan Patrick Sheridan, Miami University, Roman Slavery

Another common method of manumission was called the Manumissio testamento.

"In this form one of two things can happen: In the first condition, a slave is set free by a proclamation to do so in the master's will. In the second condition, the master entrusts his slave to another freeperson on the grounds that upon doing so, the slave be set free by the new master. In the second condition, the slave may not be immediately set free because the slave will only be freed when the new master frees him or her, and, until the slave is freed, the slave is classified as a statuliber." - Brendan Patrick Sheridan, Miami University, Roman Slavery

The third method of manumission was known as Manumissio censu.

"In this form, the slave goes before the censor and proclaims to be a freedperson [with witnesses and/or evidence], at which time, if the censor agrees, the censor will record the slave's name down as a freedperson, and thus the slave will be manumitted." - Brendan Patrick Sheridan, Miami University, Roman Slavery

Roman slaves were allowed to manage some personal property, often a small wage called a peculium.

|

| Roman coin bank depicting a beggar girl 25-50 CE. Photographed at the Getty Villa by Mary Harrsch © 2014 |

"This peculium could consist of a myriad of things including money and a slave's slave called a vicarius. The peculium could be used by the slave in many ways, but the slave was restricted in that all contracts entered by the slave involved the master, and the slave could not give his peculium to someone else so that the other person might use it to buy the slave's freedom. The slave could save peculium and buy its freedom, but this usually only happened when the peculium outweighed the slave's value." - Brendan Patrick Sheridan, Miami University, Roman Slavery

Although manumission was treated as a sought after privilege, it was not always altruistically granted. Elderly slaves were sometimes manumitted because they were no longer productive and their masters no longer wished to provide for them. If a slave was privy to incriminating information, a master might manumit them to avoid the slave providing incriminating information under torture. Slaves were also sometimes promised manumission if they served as soldiers in civil insurrections.

So, how often did manumission occur? That question has consumed scholars for decades!

"In 357 BCE Rome passed a law called the Lex Manlia imposing a manumission tax. Freeing slaves from then on would incur a 5% fee. Because 5% is one-twentieth, the tax was referred to as a Vicesima. (Livy VII.16)

This legislation was initially proposed by the consul Gnaeus Manlius Capitolinus while encamped with his army so it is said to have been passed "in castris." The purpose of the law was to reduce the number of manumissions, both the freeing of slaves and the manumission of children since it was feared some families would use manumission of their minor children to gain access to more land since there was also a 500-acre limit per male head of household specified in another law included in the Leges Liciniae Sextiae passed at that time.

H.H. Scullard, in A History of the Roman World 753-146 BC (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1980) says that based on records of these taxes, by 209 B.C.E., an estimated 1350 slaves may have been manumitted each year."

But that was more than 100 years before the widespread conquests of the Late Republic.

Apparently, the Lex Manlius had little effect on the rate of manumission even as numbers of slaves dramatically increased. Freeing slaves in an individual's will had become so widespread in the late Republic that in 2 BCE the Lex Fufio-Caninia was passed limiting the number of slaves a citizen could free in their wills.

"The Fufia Caninia made the number of testamentary grants of freedom permitted to cives Romani dependant upon the total number of slaves owned by any one Roman citizen master. One who owned from three to ten slaves was permitted to manumit one-half of them in his will; one who owned eleven to thirty, one-third of the total. If the slaves of the Roman citizen numbered from thirty-one to one hundred, he might free one fourth of them; if their numbers ran one hundred to five hundred only one in five or twenty percent, might be freed by testamentary manumission. The law further provided that no Roman citizen could free by testament more than one hundred, however many slaves he might have." - William Linn Westermann, The Slave Systems of Greek and Roman Antiquity

Six years later this law was further amended by the Lex Aelia-Sentia that restricted the rights of Roman youths under the age of 20 to free their slaves and specified that only slaves over 30 years of age could be freed although there was a mitigating provision that an exception could be granted of approved by a committee of ten persons made up of five senators and five equites. Modern scholars think Augustus promulgated these laws due to the influence of Dionysius of Halicarnassus. The esteemed historian Dionysius had pointed out that many freedmen were enriching themselves from sordid occupations such as robbery and prostitution and emphasized the danger of allowing their proliferation in the city of Rome. Being a Greek, Dionysius probably ascribed to the Athenian perspective on slave manumission. In Athens, slaves could be manumitted but were not granted citizenship as under Roman law. Athenian freedmen could not partake in government or bear free children.

|

| Bust of a Roman slave boy from the Trajanic Period 98-117 CE Photographed at The Getty Villa by Mary Harrsch © 2006 |

Like most things in life, there was a major exception to the granting of these rights, however.

"The Lex Aelia Sentia requires that any slaves who had been put in chains as a punishment by their masters or had been branded or interrogated under torture about some crime of which they were found to be guilty; and any who had been handed over to fight as gladiators or with wild beasts, or had belonged to a troupe of gladiators or had been imprisoned; should, if the same owner or any subsequent owner manumits them, become free men of the same status as subject foreigners (peregrini dediticii)... "

|

| Gladiator helmet depicting scenes from the Trojan War recovered from Herculaneum 1st century CE Photographed at "Pompeii: The Exhibit" at the Pacific Science Center in Seattle, Washington by Mary Harrsch © 2015 |

"...'Subject foreigners' is the name given to those who had once fought a regular war against the Roman People, were defeated, and gave themselves up...."

"...We will never accept that slaves who have suffered a disgrace of this kind can become either Roman citizens or Latins (whatever the procedure of manumission and whatever their age at the time, even if they were in their masters' full ownership); we consider that they should always be held to have the status of subjects." - Selections from the Lex Aelia Sentia

But what does the archaeological record tell us about actual numbers of freedmen in relationship to other social groups?

G. Afoldi, citing a 1972 study of Roman-era inscriptions found in Italy in his paper Die Freilassung von Sklaven und die Struktur der Sklaverei in der romischen Kaiserzeit (The release of slaves and the structure of slavery in the Roman Empire), discovered that of 1,126 persons of servile origin who died before the age of 30, 59.3 percent were freed, 40.7 percent were still slaves. Of 740 persons who died over the age of 30, 89.3 percent were freed, and only 10.7 per cent had remained slaves. He concluded that, in view of these statistics, a slave could probably count on being freed as a matter of course.

However, Thomas E. J. Wiedemann, in his 1985 article "The Regularity of Manumission at Rome" expressed his opinion that Afoldi's inscriptions represented a highly atypical sample.

"Slaves who did not have the qualities to attain manumission were clearly less likely to be commemorated by means of a (relatively detailed, therefore costly) inscription; slaves who were considered fideles, but died young, might be so commemorated. More particularly, a freed slave's heirs would be keen to preserve a public record of his manumission in the form of a funerary inscription. Futhermore, these inscriptions give undue emphasis to those slaves and freedmen who had easy access to their dominus. As Alfoldi noted (p. 116) 98 percent of the surviving inscriptions are from the context of the familia urbana. The obvious explanation for why so few freedmen are attested from the familia rustica is that very few agricultural slaves were actually freed."

|

| A partially restored Villa Rustica at Boscoreale near Naples, Italy. Photographed by Mary Harrsch © 2007 |

Weidemann also dismisses an analysis of epitaphs from imperial slaves indicating that manumission was regularly achieved between the ages of 30 and 35.

"The imperial household was not just different in scale from others; it also followed different procedures of manumission. The legal restrictions did not apply to the emperor; his slaves were not manumitted vindicta or testamento, but simply declared to be free," Wiedemann observes.

A study of the Osyrhynchus Papyrir (up to vol. XLII) from Roman Egypt revealed of 46 slaves or freedpersons ranging from 3 to 65 years, 8.3 percent of those under 30 had been freed but of those over 30, fully half had been freed. Wiedmann points to the small sample size, though, as insufficient to provide meaningful statistical evidence.

Wiedemann then turns to the literary record to examine Roman society's acceptable norms for manumission. Citing two examples in Martial's epigrams, Wiedemann concludes, "A Roman wanted to believe that if a slave served him faithfully, he would be rewarded with the freedom he deserved."

He goes on to point out though, "If manumission was the due reward of the servus fidelis, then it followed that a slave-owner did not have any obligation to free a slave who had demonstrated that he was not fidelis. There is plenty of evidence that masters who were displeased with their slaves would include in their wills a clause prohibiting slaves in question from ever being freed...Thus the ideal that loyal service deserved manumission also implied that a master might be acting justly if he refused to free his slaves: he need have no moral compunction so long as he persuaded himself that his slaves had failed to show him the loyalty a master deserved (cf. 'nullo merito meo'). One suspects that the formula 'nulla fides > nulla manumissio' may have been adduced very much more frequently in real life than the formula 'fides > manumissio'."

I think this viewpoint that Rome's wealthy slave owners were probably too greedy to reward faithful slaves with manumission does not take into account the fact that freed slaves were not simply allowed to go their separate ways when manumitted. The prevailing practice was for freed slaves to become clients of their former master.

"Roman societal patronage was highly based around the Roman ideals of fides or loyalty. Clients were loyal supporters of high standing families and at the head of those families were the patronus, or their patron. For this loyalty, the patron rewarded their loyal clients with gifts of food and land. If a client needed any sort of legal representation or aid they called upon their patron for support. Patrons often handed out sportulas, which were monetary handouts for their support and loyalty. The patron received not just loyalty from their clients but they also had the respect, men for guarded escorts, and their political support." - Roman Patronage in Society, Politics, and Military, a collaborative website of Pennsylvania State University

Another issue not mentioned in the above quote is the operation of businesses that produced income for the patrician class. Patricians were not supposed to engage openly in business activities so these revenue-generating activities had to have the appearance that they were being operated by others. These positions could be held by freedmen. Patrons not only provided monetary handouts for a client's support but also provided loans for businesses operated by their freedmen-clients.

Add to this the problem of a slave-owner appearing to be greedy if slaves were not freed while reasonably young.

Wiedemann states, "In his invective against Piso, one of the grounds on which Cicero attacks him is his parsimoniousness. He argues that, while a luxurious lifestyle is, in principle, immoral, there is a particular kind of luxuria (conspicuous consumption) which is expected of a public figure. But this was not to be found in Piso's household; Piso was so unwilling to put his wealth to public use that he was not even prepared to spend money to acquire any new slaves, so that (In Pisonem 67):

servi sordidi ministrant, nonnulli etiam senes; idem coquus, idem atriensis (the servants who minister to the mean station positions, some even old men; the cook is the same thing, the same as the doorkeeper)

Although Wiedemann thinks Cicero is referring to the generally recognized custom that slaves who serve at a banquet ought to be young and handsome, I must point out his quote also refers to the cook and the doorkeeper, not usually present in the banquet setting.

"For the Roman upper aristocratic ruling class public appearance was extremely important. When traveling through the city and the forum the Roman elite desired to be recognized or recognized for their status and rank. To accomplish this they wore distinctive clothing and jewelry to help signify their status. Equestrians wore specifically colored cloth stripes on their togas or tunics to signify their statuses. The senators and patricians also wore wider specifically colored cloth stripes to signify their rank. The upper-class patrons wanted to show they had power and made certain to remind their clients of this by their mannerisms and dress." - Roman Patronage in Society, Politics, and Military, a collaborative website of Pennsylvania State University

So, if slaves were regularly manumitted after a period of service, what was the socially acceptable length of time a slave could expect to serve? Wiedemann examines a number of legal cases and finds several references to periods of five years although that may be an average as a number of cases cite longer periods and some even shorter periods.

Perhaps more telling is a quote from Cicero's Eighth Philippic in which Cicero exhorts the Senate to resist Antonius' dictatorship.

Etenim, Patres conscripti, cum in spem libertatis sexennio post sumus ingressi diutiusque servitutem perpessi quam captivi servi frugi et diligentes solent (In fact, Conscript Fathers of the Senate, I have the hope of freedom, that after six years, we are good and diligent slaves taken in war and have endured slavery longer than the customary [period].

Cicero is referring to the six years since Gaius Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon but uses its length of time as a metaphor for a slave's length of servitude.

Wiedemann points out, "Clearly Cicero could not use this analogy between slavery and submission to the rule of Caesar and Anthony if his senatorial audience did not believe that it was reasonable for a slave-owner to grant freedom after he had had possession of a slave for six years of adult labour — assuming of course that the slave was frugi et diligens."

So it appears slavery in Rome was not a lifelong sentence as in other ancient cultures and manumissions occurred regularly.

References:

Thomas E. J. Wiedemann. (1985). The Regularity of Manumission at Rome. The Classical Quarterly, 35(1), 162-175. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/638813

Patrick, B. (n.d.). Roman Slavery. Retrieved August 11, 2017, from http://www.vroma.org/~plautus/slaverysheridan.html

Aföldi, G. (1972). Die Freilassung von Sklaven und die Struktur der Sklaverei in der romischen Kaiserzeit (The release of slaves and the structure of slavery in the Roman Empire). Rivista Storica dell' Antichitá , 2, 97-129.

Roman Patronage in Society, Politics, and Military. (n.d.). Retrieved August 11, 2017, from https://sites.psu.edu/romanpatronagegroupdcams101/societal-patronage/

Collaborative website of the Classics Department of Pennsylvania State University

Cicero, In Pisonem, 67.

A Kindle preview of a bit of a tongue-in-cheek guide to Roman slavery:

Additiional suggested reading:

|

|

|