|

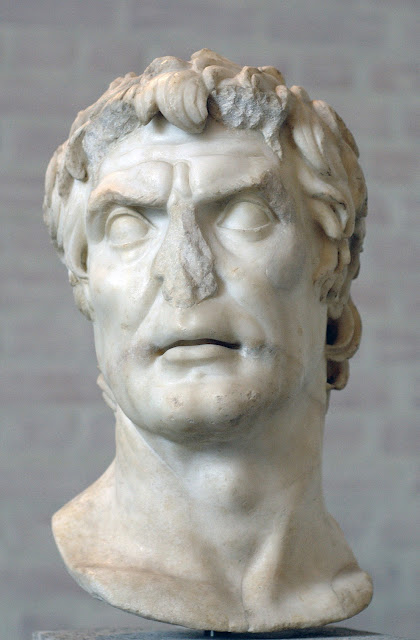

| Reconstruction of a cubiculum in a Roman villa in Oplontis near Naples, Italy courtesy of the University of Michigan's exhibit, "Leisure and Luxury in the Age of Nero." |

I've been studying more about the material culture of Pompeian Households and learned that since the excavations in Pompeii of the late 19th century, archaeologists have associated narrow wall recesses with bed installations, calling them bed niches and using their presence to determine a room to be a cubiculum (bedroom). However, in the study of atrium houses conducted by current archaeologist Penelope Allison, correlating the find assemblages in 84 small closed decorated rooms off the front halls of these houses, less than 15 percent were found to have these types of recesses and only 16 percent of this subset contained identifiable evidence of bedding with only one actual instance of bedding found in conjunction with the so-called "bed niche." She points out, though, that evidence of bedding may have gone unrecorded in the earliest excavations. However, ten of thirteen rooms with recesses were excavated in the 20th century and she thinks such evidence would not have gone unrecorded in those structures. Therefore, she concludes that there is no direct relationship between evidence of bedding and recesses attributed to "bed niches".

"More common were assemblages consisting variously of the remains of small chests and caskets; a variety of bronze serving, pouring, and storage vessels; ceramic vessels that were usually small and of fine quality, but occasionally included large amphorae; and items related to dress, toiletries, needlework, and lighting. These were found, generally in small quantities, in thirteen to eighteen decorated rooms of this type." - Allison, Penelope M.. Pompeian Households: An Analysis of Material Culture (Monograph Book 42) (p. 72). Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. Kindle Edition.

Since things like toiletries and needlework sounded more "bedroom" related, I was a little confused by this conclusion but she went on to clarify it:

Actual evidence of bedding was rare, however, implying that decorated rooms of this type functioned as a type of “boudoir” rather than as a sleeping space. - Allison, Penelope M.. Pompeian Households: An Analysis of Material Culture (Monograph Book 42) (p. 72). Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. Kindle Edition.

In the case of the House of the Prince of Naples, though, she associates the finds there with "industrial" use, a space where craftsmanship was practiced. That actually coincides with my theory that cubiculum (c), immediately to the left of the front entrance, could have served as a physican's treatment room due to the discovery of a surgical instrument, an apotropaic figurine of a herm, and a human skeleton (as well as other surgical instruments and physician-related tools elsewhere in the house.)

However, earlier in the book Allison observes that there are multiple cases where skeletons are found in close proximity to "robber" or access holes as was the case in cubiculum (c), that I thought may have been an unsuccesfully treated patient. Allison proposes that somehow the holes may have been created by these victims of the eruption and not salvagers or looters. I'm hoping she will explore this proposal more in a later chapter.

I found other things she mentioned quite enlightening as well. She points out that 19th century archaeologists were not really interested in human remains or evidence of destroyed organic material like the wood of cabinetry or storage chests. They did make note of metal hinges, though, whenever they found those. She also said they rarely mention unmarked amphora either. I noticed that in the find summaries for the House of the Prince of Naples, only amphora with inscriptions were noted. They also virtually ignored pottery or glass fragments, too. Flinders Petrie must have been appalled!